Can growing civic knowledge help move us closer to 100% student voter participation?

How one community college’s civics module changed the way students engage with democracy.

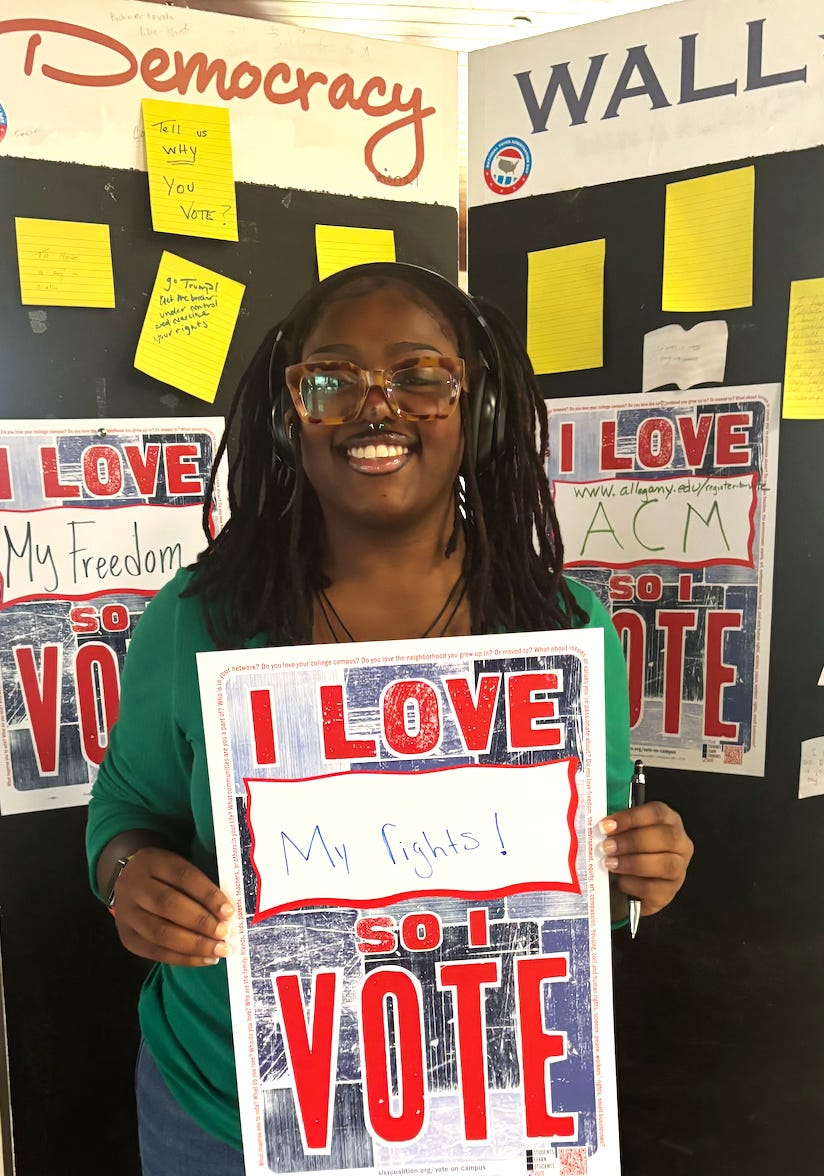

As professors at Allegany College of Maryland (ACM), a rural-serving 2-year public college in the Appalachian foothills of Western Maryland, we serve a largely first-generation, low-income student population. Over 80% of our students are the first in their families to attend college, and nearly 90% receive financial aid. Many arrive on campus without a strong foundation in civics education.

For years we have observed how misinformation and the mounting pressure facing democratic norms in our country have impacted our community, confronting us with a vital question: Can civic knowledge be taught in a way that not only informs students, but also activates them?

At ACM, we set out to explore that question directly. Over the past two years, our team designed and tested an academic intervention with one goal: to determine whether embedding a civics module in a general education course could increase students’ understanding of democracy, and ultimately, their engagement in it.

Through the course of our research, we asked two central questions:

What is the effect of an educational intervention on student civic learning?

Can structured, college-level civic instruction move students closer to the ballot box?

Our methodology

We originally designed our study using a Solomon four-group structure, a methodology meant to isolate the effects of the civic education module from the effects of simply taking a pretest. The intent was to capture how instruction, testing, and their interaction influenced outcomes.

Due to low enrollment in two of the groups, however, our analysis focused on two primary cohorts:

Group 1: Received a full Democracy 101 module and completed both a pretest and posttest

Group 2: Completed the same pre/post survey but followed a standard Sociology 101 curriculum, with no civic instruction

Despite the adjusted design, this comparison yielded valuable insights into the impact of targeted civic instruction.

The Democracy 101 module introduced students to democratic principles, local governance, media literacy, and voting systems. Through video lectures, assigned readings, and structured discussions, students were challenged to apply civic concepts to contemporary political realities.

What we found

The clearest takeaway from our study? Knowledge works.

By the end of the semester, students in the Democracy 101 group showed a statistically significant increase in factual civic knowledge. The effect size was moderate but meaningful. Even a single-semester module can move the needle on what students know about democracy.

We also conducted a factor analysis of the survey data, which revealed three core components of civic engagement:

Democratic Knowledge: Understanding government systems, rights, and the nature of regimes

Civic Attitudes and Efficacy: Belief that voting matters and individuals can influence policy

Media Skepticism: Awareness of misinformation and critical engagement with news content

These findings reinforce a crucial point: Civic engagement requires more than facts. It demands confidence, critical thinking, and trust in the democratic process.

Unfortunately, while we linked survey responses to official voter records from Maryland’s May 2024 primary, the turnout rate was too low for statistically meaningful comparisons. We had hoped to draw a direct line between instruction and ballot-box behavior, but the data didn’t support that conclusion.

Key takeaways

Our research demonstrated that civic knowledge can be taught and that students, especially in underserved regions, respond to relevant, well-designed instruction. The knowledge gains observed in Group 1 weren’t incidental. They were the product of intentional pedagogy, grounded in real-world application.

However, we also learned that knowledge alone isn’t enough.

The more pressing challenge is conversion: how to transform understanding into action. While students reported greater confidence and awareness, few cast votes. The gap between civic learning and democratic participation remains a difficult one to bridge.

What comes next?

In 2022, ACM was recognized by the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge for achieving the highest voter registration and turnout among Maryland’s two-year institutions. That recognition underscores our students’ potential and our campus-wide commitment to civic engagement.

The Democracy 101 module builds on this momentum, but it’s only one part of the solution.

We see tremendous value in expanding applied learning opportunities, such as:

Voter registration drives embedded into coursework

Public debates and simulations centered on local policy

Partnerships with community organizations tackling real-world issues

Civic education shouldn’t be confined to a single course or a single semester. It should be integrated across disciplines and supported throughout the student experience.

Future research can take this work further. Larger and more diverse samples would enhance generalizability. Full implementation of the Solomon design could help isolate causal effects. Qualitative methods like interviews and focus groups might help us understand why some students vote while others don’t, even after learning how.

Importantly, future studies might also track participation in general elections, which typically see higher turnout and may offer a more accurate measure of intervention effects than primary turnout alone.

The upshot

Our findings can be viewed as both a challenge and an invitation to educators, organizers, and advocates working toward 100% student voter participation. If we’re serious about creating a more inclusive and representative democracy, civic engagement efforts must begin where students are, including at rural community colleges that are often excluded from national conversations.

Our study shows that structured civic instruction can significantly improve knowledge. And though often overlooked, community colleges are uniquely positioned to lead this work. Just as importantly, students at institutions like ACM - who are rural, diverse, largely first-generation, and largely working class - are central to these efforts and their role in helping every college student participate in elections.

We believe our research is one small step in that direction.