Does college work for democracy?

There is strong evidence that college increases civic engagement even after we account for selection effects. To reach 100% participation we need to know much more about how and why this happens.

In 2002, the U.S. Department of Education began an effort to track student trajectories from the beginning of high school into college, the workforce, and beyond. The study was nationally representative and included high quality data about the educational experiences students were having (including what courses they took and the grades they received) as well as workforce and civic experiences outside the classroom. Twenty years after this study began, we can clearly see how certain experiences in high school and college affect the economic and civic trajectories of students.

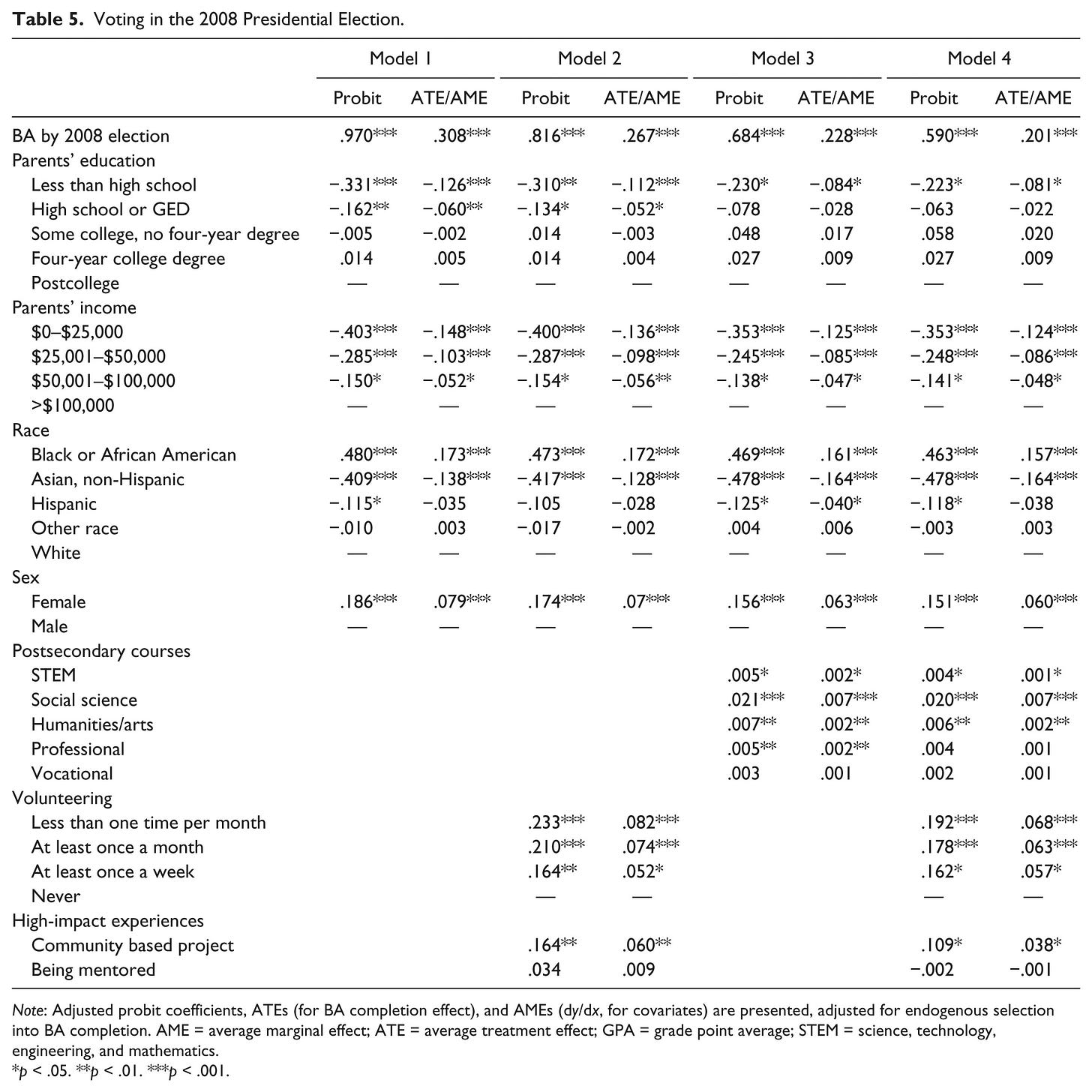

In 2019, my colleague Alanna Gillis and I published new research showing that college attendance and completion increases voter participation. This effect is clear even after we control for the fact that people who choose to attend and complete college are already more likely to vote. There is something about what happens at college that makes students more likely to vote than they otherwise would be.

But we don’t know exactly what it is. While the data is suggestive that experiences like taking courses in the humanities and having volunteering experiences are important, the ELS data isn’t robust enough to prove this beyond a doubt. And even if we did have this data, there are still more important unanswered questions that we need to explore in order to inform policy and strategies in the field. Are there some types of institutions that have stronger civic impact on students than others? What mechanisms are driving these impacts?

We already know what it would take to have a much better understanding of what factors shape the emergence of civic behaviors and democratic imagination in students. Over the last 30 years, sociologists have been able to study social, behavioral, and biological linkages across the life course as a result of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (“AddHealth”). This study engaged a nationally representative sample of 20,000 adolescents in the 1994-1995 school year and has followed up with them in five waves of data collection since then. I believe we should launch a similar effort tracking civic behaviors.

In the coming months, I’m going to be working with colleagues in the Student Vote Research Network to explore what a longitudinal study to track the emergence of civic behaviors and democratic imagination might look like. The work that civic educators do every day is so essential to our democracy. They deserve to know exactly how and where and why it has an impact.

Our colleges must work for democracy and our democracy must work for colleges. Colleges must prepare students for the workforce and civic life, and the civic experiences we provide in college should make students more likely to stay in college and succeed and graduate. The civic health of our students and our communities is too important to leave to chance. It is deserving of the same kind of rigorous study that we use to evaluate physical and mental health. Please reach out to me by replying to this email if you want to get involved in developing such a study!

Dr. Andrew Perrin is part of the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University and a Professor of Sociology in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. He is a cultural and political sociologist working on issues of democracy, including civic engagement, effects of higher education, and public deliberation. His research explores what people need to know, do, and be to be effective, creative, thoughtful democratic citizens. He is author or co-author of five books, including Citizen Speak: The Democratic Imagination in American Life (University of Chicago Press, 2006), and American Democracy: From Tocqueville to Town Halls to Twitter (Polity, 2014)