How one college is combating student voter disillusionment in 2024

Changing times call for changing tactics

At Columbia College Chicago (CCC), we thought we had arrived at a formula that worked for our Ask Every Student approach to voter engagement. Beginning in 2019, the Columbia Votes team – comprised of Voter Registration Geniuses (student workers I’ve trained) and me – visited every section of our college-wide first-semester freshman course, Big Chicago, to do a presentation we described as “voter education, motivation and registration.”

The presentation began with an exploration of the barriers that keep students from voting (“My one vote won’t make a difference,” “I don’t know enough about the candidates and the issues,” and so on) and countered them with information about the power of the youth vote and strategies for being an informed voter. And it worked! Our voting rate rose from 56% in 2016 to nearly 72% in 2020 according to the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement’s CCC Campus Report.

But this year, we could sense that something was different. Students weren’t as interested in our pitch. They were a mix of discouraged about the state of the country and the world, angry about the direction things were going on the issues they cared about, and disgusted with elected officials who didn’t seem to represent them. Voting seemed pointless to them at best, and like acquiescence to a broken system at worst.

But they still cared. Just as we knew four years ago that very real barriers, not apathy, were keeping young people from voting then, we knew that frustration, not apathy, was keeping young people from engaging now. They still cared – a lot – about the state of their communities, the country and the world. They just didn’t see how voting would help.

A revised approach

Instead of talking about barriers and how to overcome them, we now start our presentations with a simple question: “What do you care about?” And then we listen.

Students are eager to share their concerns. They speak about reproductive health care, queer rights, the war in Gaza, police brutality and climate change. As a nonpartisan voter engagement group, we can’t and don’t take a position on any of these things, so we just listen, welcoming everyone to add to the discussion.

Connecting voting to positive change

Once students have shared the issues that they care about, we ask another question: “How do you make positive change around those things?”

Again, they tell us: They’ve been posting to social media, talking to their friends, participating in protests, signing petitions.

Those are great things to do, we tell them. But there are people who have more influence over those issues than we do–people who can actually make a difference when they are in positions of power. Those people are elected officials, and if you are a voter, you can help choose who they are and also lobby them to reflect your values.

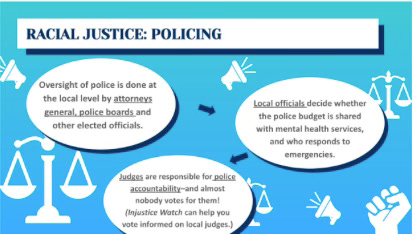

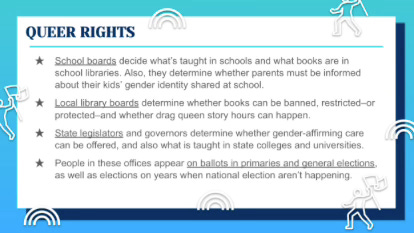

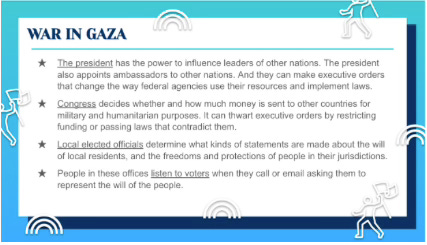

And then we walk through several slides that simply lay out, in a non-partisan fashion, who does what around the issues they care about:

In other words, we tell them, elections matter.

Bringing the conversation back to the ballot box

Once we’ve shifted the discussion back to voting and elections, we provide students with reliable resources to learn about the candidates. And we encourage them not to sit out the top of the ticket. “We’re not excited about a rematch of Biden vs. Trump either,” we say, “but it’s still important to vote for one or the other because if you don’t, you just doubled somebody else’s vote who disagrees with your values.”

The mood in the room is noticeably different with this approach. Students are engaged because they feel heard. And they reciprocate by listening to us as we explain how the political process works, and how to learn about candidates at the national, state and local level.

Listening first in order to educate better

This kind of information – the “education and motivation” that accompanies voter registration – is essential right now. We are in an age of news avoidance, compounded by local news deserts and an overwhelming amount of social media misinformation and disinformation. As a result, our students don’t know the roles of specific public offices, who the candidates are, what they’ve done, and what they say they’ll do. That makes it our job to be trustworthy sources of that information.

There is huge power in a peer-to-peer approach that includes listening to students’ concerns, helping them see the power of elected officials to influence those things and their own power to influence elected officials, and then inviting them to register and make a plan to vote. The Institute for Democracy & Higher Education has long encouraged and provided guidance for discussing politics in the classroom. Facilitating discussions about controversial issues, without taking sides, is known to increase civic engagement and promote voting among college students.

It’s also important to respect the ways our students are already civically engaged. By affirming the value of what they are already doing–going to protests, signing petitions, posting to social media–we can offer voting as another avenue for them to achieve their objectives. In other words, we aren’t promoting voting as the only means of expression; we’re promoting it as an additional strategy to help them make an impact.

The upshot

We don’t have data yet (that would be a good subject for someone to study!) but we do have anecdotal evidence that students are responding more positively to our new approach. We see it in the concerns they raise, the questions they ask, and the action they take when we help them register to vote. If all goes well, we’ll also see it in the election turnout results.

Sharon Bloyd-Peshkin is a Professor of Journalism at Columbia College Chicago, the founder of Columbia Votes and the Faculty Fellow for Civic Engagement.