It is unconstitutional to discriminate against voters on account of their age...

...so why do such extreme age-based disparities persist in American elections? The democracy movement has extraordinary untapped opportunities to use the 26th Amendment to achieve big change.

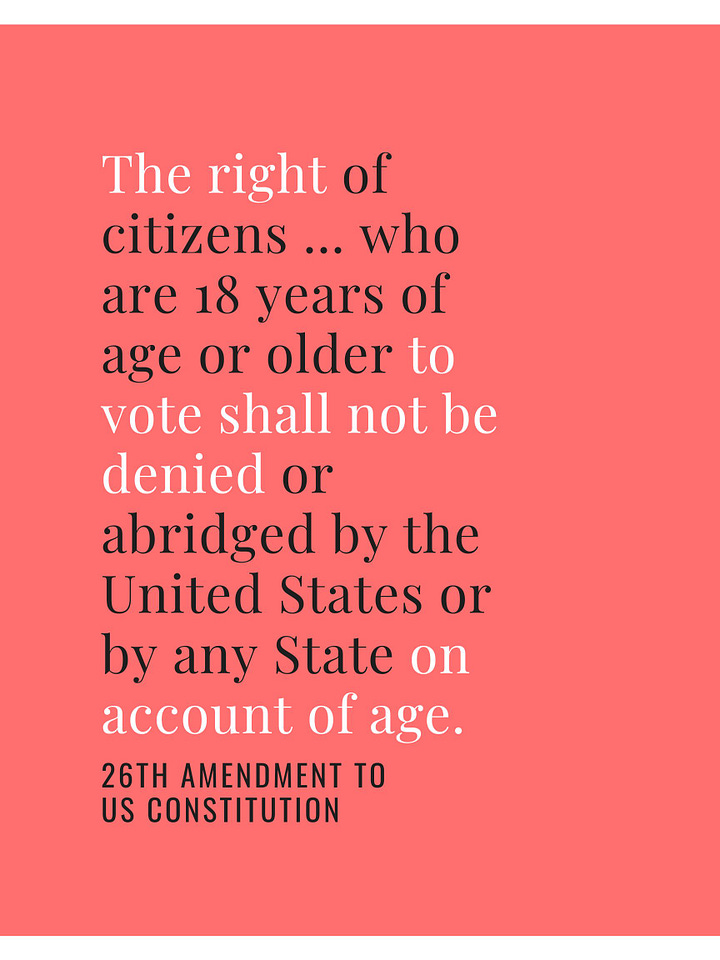

The 26th Amendment didn’t only lower the voting age. It barred age discrimination in elections.

Many people know the 26th Amendment as the amendment that lowered the voting age to 18 on the heels of the mandatory draft during the Vietnam War. But it does much more than lower the voting age. The text - which mirrors the 15th amendment enfranchising Black men and the 19th amendment enfranchising women - gives voters protection from the denial or abridgment of the right to vote “on account of age.” This right has been recognized by the courts.

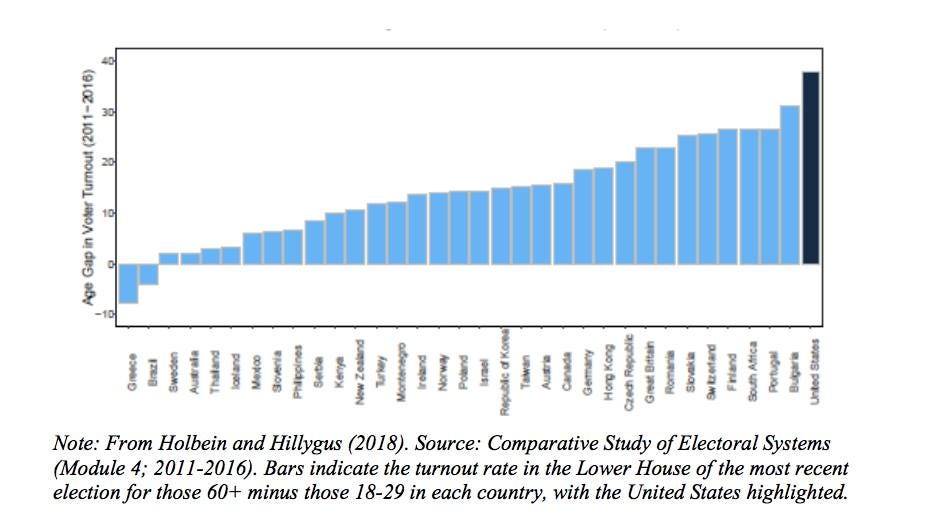

But age discrimination persists in U.S elections in violation of the 26th Amendment. This is not normal; the U.S. consistently has one of the largest gaps in voter turnout between younger and older voters of any nation.

As Jake Grumbach, Charlotte Hill, Lauren Kunis, Sam Novey and others have written on State of the Student Vote, policies such as those pertaining to voter registration and voter ID often disadvantage young voters the most. Young voters face a range of unique obstacles which I’ve previously outlined, which individually and cumulatively contribute to “The Unfulfilled Promise of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment.”

Simply put, we must more seriously consider and examine the impact of our electoral system "on account of age" to understand, monitor, and most importantly - respond - to serious gaps in election administration and voting rights.

The Constitution recognizes young people as a “protected class” of voters. This means they cannot be the target of voter suppression.

In February, the Rutgers University Law Review published the first legal volume dedicated to the Twenty-Sixth Amendment since its ratification just over 50 years ago.

The publication followed a law symposium bringing together a range of voices – undergraduate students, election administrators, college administrators, undergraduate and law professors, organizers and advocates, nonprofit leaders, developmental scientists, and constitutional rights litigators – to address “Voting Rights Reform: The 26th Amendment, Youth Power, Lawmaking, and the Potential for a Third Reconstruction.” The resulting legal volume features several of these contributors’ articles, and benefits from the rich discussion generated by all participants.

My introduction to the volume, The Future Is Unwritten: Reclaiming the Twenty-Sixth Amendment, offers an overview of the novel articles featured, and sets a course for reclaiming this forgotten and overlooked constitutional right: Where will the next fifty years lead us as we approach the centennial of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment?

“The Future Is Unwritten” tracks the cross-partisan history of the 26th Amendment – the quickest to be ratified in U.S. history – and offers some detail about how a tipping point was finally reached on the youth franchise in the late sixties. (TL; DR: it was led by young organizers and supported by a wide coalition across the nation, inside and outside of legislatures, after a 30-year boil). It explains the current state of affairs, and the tension between the historic and recent interpretations of the amendment, including an attack arising out of Texas which is currently pending before the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals regarding access to vote by mail free of age discrimination.

“Yet, despite the Twenty-Sixth Amendment’s nearly unanimous ratification and the prominent role of youth leadership throughout the Second Reconstruction (1954-1967), which catapulted its constitutionalization, youth voting rights are not widely perceived today within a systemic framework of a constitutionalized protected class (youth) and classification (age) with regard to ballot access.”

-Introduction, The Future Is Unwritten

The central argument I advance is the importance of recognizing young voters as a “protected class,” and age as a “protected classification” with regard to ballot access. The U.S. Constitution, and state constitutions, recognize certain protected identities (classes) with respect to the right to vote – such as race or color (the Fifteenth Amendment); sex and gender (the Nineteenth Amendment); and wealth (the Twenty-Fourth Amendment). Just as these amendments forbid denial or abridgment of the right to vote “on account of” race, color, sex, or inability to pay poll taxes or other taxes, the Twenty-Sixth Amendment forbids denial or abridgement “on account of age.” These protected classifications are meant to be read alongside the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees equal treatment under law.

Just as the Constitution says women or African Americans cannot have their right to vote denied or abridged on account of gender or race, neither can young voters (or other voters) on account of age.

The 26th Amendment has been abandoned by our society. The Future is Unwritten seeks to change that.

“Notwithstanding the fundamental principles established upon ratification of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment that embraced the cross-partisan recognition that youth enfranchisement is critical for democracy and that investing in our youth is as American as apple pie, the burgeoning Twenty-Sixth Amendment modern jurisprudence remains caught in the crosshairs of the ‘voting wars’ playing out in the federal judiciary. The repercussions of this forgetting or outright abandonment of this constitutional right are evident at every step of the youth voter engagement process: pre-registration, voter registration and portability, in-person voting location and proofs, and mail voting .

-Introduction, The Future Is Unwritten

Given that the Twenty-Sixth Amendment jurisprudence has laid nascent for the better part of forty years, forging a path forward to reinvigorate our popular understanding and recognition of the constitutional right will require laying a foundation with public education infused by research and data analysis, and strategic organizing and advocacy that builds collective experience and confidence.

The various contributing articles by a range of voices set out to do just that:

U.S. Election Assistance Commissioner Ben Hovland and Federal Elections Commission Special Counsel Phil Olaya, “Shaping Future Impact of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment: How Lessons from the 2020 Election and Voting During the COVID-19 Pandemic Are Instructive for Engaging the Next Generation of Americans.”

Law Professor Joshua A. Douglas, “State Constitutions and Youth Voting.”

Constitutional rights litigators from NYCLU (Perry Grossman) and ACLU (Adriel I. Cepeda Derieux), “Reform Begins at Home: Integrating Voting Rights Litigation and Advocacy in Progressive States.”

Duke University Professor Gunther Peck and his six undergraduate student co-authors, “Provisional Rights and Provisional Ballots in a Swing State: Understanding How and Why North Carolina College Students Lose Their Right to Vote, 2008-Present.”

Voting rights attorney Valencia Richardson of the Campaign Legal Center, who is a former Louisiana-based student ambassador-turned-board member with The Andrew Goodman Foundation, “Leveraging Civil Rights Statutes to Empower the Youth Vote.”

Bard College Vice Presidents, Directors, and Professors Jonathan Becker and Erin Cannan, “Institution as Citizen: Colleges and Universities as Actors in Defense of Student Voting Rights.”

Developmental Scientists Laura Wray-Lake & Benjamin Oosterhoff, “Using Developmental Science to Inform Voting Age Policy.”

Cara Suvall, Clinical Law Professor and Director of the Vanderbilt Youth Opportunity Clinic, “Out Before the Starting Line; Youth Voting and Felony Disenfranchisement.”

I hope you’ll explore these articles!

It will take all of us to bring the 26th Amendment to life.

Over twenty years ago, I myself was a very active young organizer; I joke that my third major was in organizing. Since then, I have had the privilege to work with a range of practitioners in the democracy movement — generations of youth leaders and multigenerational organizers on various issues, skilled advocates across the country, data analysts and scholars, constitutional rights attorneys, election administrators and elected representatives, higher education and non-profit leaders, concerned community members, and more. Essential to the process is breaking the silos and bringing a range of voices and experiences to the table. The protection of constitutional rights is not something that lawyers alone can accomplish.

In the coming weeks, we will be sharing more summaries of the articles from the Rutgers University Law Review’s Twenty-Sixth Amendment symposium volume, and I hope you’ll read them and think about how you can join this conversation. Whether you or your peers are directly experiencing voting systems that discriminate against young voters; getting to the polls and are civically engaged; studying how young voters are impacted by voting policy and practice; administering elections on the local, state, or federal level; or educating the public about the rights guaranteed by the 26th Amendment, you are advancing this work — and this constitutional right — in powerful ways. I look forward to working with you in the fight for our future.

Yael Bromberg Esq., is a constitutional rights attorney and Rutgers Law lecturer who served as faculty advisor for the Rutgers University Law Review’s Twenty-Sixth Amendment symposium volume — the first legal volume dedicated to this constitutional right since ratification over 50 years ago. She is a leading national expert on the Twenty-Sixth Amendment whose work has been dubbed “groundbreaking” and a “legal and organizing call for action.” Bromberg is Principal of Bromberg Law LLC where she primarily practices democracy law, Of Counsel to a plaintiffs’ side labor and employment law firm, and has served as special counsel and strategic advisor for The Andrew Goodman Foundation. Follow her on Twitter: @YaelBromberg