After years of progress toward racial parity in college student voting rates, the 2022 midterms saw a regression toward larger turnout gaps between white and non-white students, according to Tufts University’s National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement (NSLVE). While factors like education and income tend to mitigate differences in voter turnout to an extent, they often do not tell the whole story. Recent work has found that factors like the racial context (i.e. how many people like you there are in a community), and voter identity (thinking of yourself as a voter) are crucial to increased voting among groups considered to be low propensity voters (such as young people and members of some minority groups). Our analysis reveals that student voting gaps continue to exist between different racial groups and types of institutions. However, just as colleges vary in terms of location, student body population, and selectivity, we identified other key factors that strongly predict and mitigate racial disparities in voting.

Ahead of the 2024 presidential election, we explored campus-level data from the 2020 and 2016 presidential elections across more than 1200 institutions to uncover how racial gaps in voting manifest across different institutional types, contexts, and demographic makeups, as well as what factors may impact turnout gaps within each institution of higher education. We find that, controlling for other factors, nonwhite students vote at higher rates when they attend institutions with more ethnoracial diversity. As a result, these same institutions tend to see smaller turnout gaps between white and non-white students.

Our Process

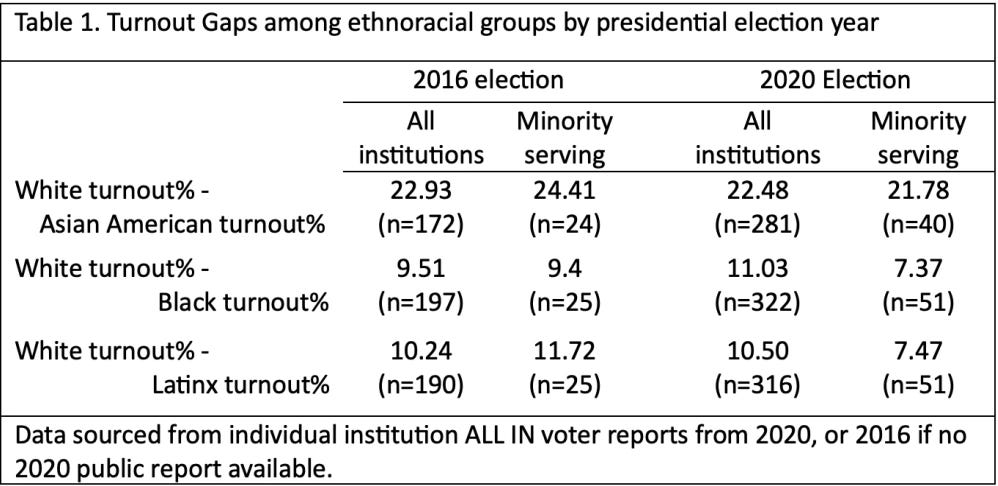

To collect the data we needed, we hand-coded over 500 campus reports from institutions that participated in the All IN Campus Democracy Challenge, created a dataset of colleges and universities, and calculated the average voter turnout gap between white and nonwhite students. We found that in 2016, the turnout gap was marginally larger at minority-serving institutions (MSIs) than it was for all institutions. In 2020 this changed and the turnout gap was significantly lower at minority-serving institutions (see Table 1 below). For Asian and Hispanic students, the turnout gap remained practically unchanged across all institutions from 2016 to 2020, but the gap decreased by about 3% at MSIs for Asians and 4% for Latinx students. For African American students at non-MSI’s the gap increased in 2020, but decreased 2% at MSI’s. These numbers suggest that efforts to increase minority turnout and civic engagement at minority-serving institutions in 2020 may be meaningfully more effective than similar efforts at all other colleges and universities.

What creates these gaps?

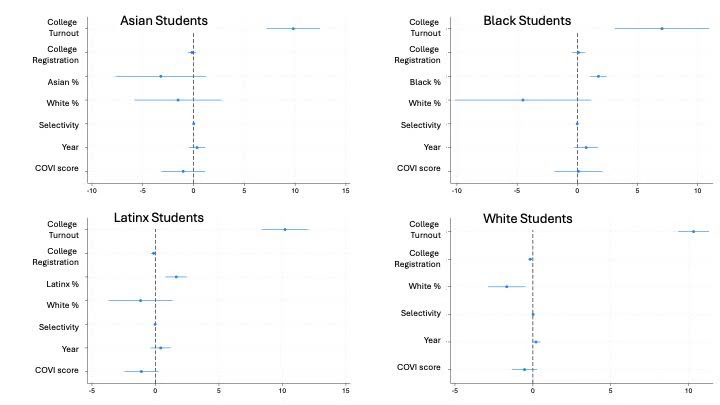

Using a multivariate regression, we examined the factors that shaped turnout for each racial group. We also included the impact of institutional characteristics such as selectivity, institutional diversity, collegewide turnout, and location.

Results

When an institution has higher overall voter turnout, all races will also have a higher turnout. However, the type of institution impacts the extent to which turnout among nonwhite ethno-racial groups are impacted by overall turnout rate. For example, in both 2016 and 2020, Black students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) voted at higher rates than Black students at non-HBCUs. In 2020, turnout among Black students at HBCUs was 64.83% compared to 59.9% at non-HBCUs. The next figure plots the impact of each variable along with 95% confidence intervals to show which variables are most important in predicting each racial group’s aggregate turnout.

Among Black and Hispanic students, as the proportion of students within their own racial group at a university increases, so does the turnout among that racial group. Surprisingly, White students have a negative correlation between enrollment proportion and turnout, and there is no significant trend for Asian turnout (shown in “% same ethno-racial” on Table 2).

Our findings confirm that two major theories of voter turnout also apply to the college level. First, voter culture is needed to mobilize voters: if there is a strong voter registration culture, as well as greater diversity within the student body population, turnout among non-white students will increase. Second, a greater presence of individuals in a co-ethnic group is a strong mobilizing factor for turning out to vote.

What we know and where to next?

To understand voter turnout among any multi-racial group, it is important to determine if structural inequities impact racial gaps in voting. Perhaps surprisingly, we found that institutional registration rates did not impact turnout when looking at each individual racial group, and neither did how selective the institution is (measured as acceptance rate).

However, more work is needed to understand all of the factors that could contribute to the existing inequalities in voting within institutions. One additional area that future research should account for is the use of absentee ballots at both the institutional and state levels.

The upshot

Our evidence shows that race continues to be a factor in turnout among young voters who are pursuing higher education, but it remains unclear why campus diversity correlates with smaller racial turnout gaps. By continuing to research this issue across multiple election cycles (including the 2024 election once detailed student voting statistics from that election become available) and with a specific focus on the cultural or organizational differences between minority-serving institutions and the rest of the higher education community, we can achieve a greater understanding of how voter turnout gaps present themselves at the campus level, with an eye toward reducing or eliminating those gaps.